Continuous Glucose Monitoring System Graph Non Diabetic

Yes, you read the title correctly. I do not have diabetes and I willingly chose to wear a CGM.

Overall, this was an eye-opening "CGM experiment" and this post covers what I learned as a non diabetic from wearing a continuous glucose monitor (aka CGM).

My CGM Experiment: What I Learned as a Non-Diabetic From Wearing a Continuous Glucose Monitor

I wasn't sure I'd write much about it, but when I asked folks on my email list if they'd be interested in hearing about this CGM experiment (which I lovingly referred to as my semi-bionic arm), the response was HUGE.

I even polled my Instagram followers in my stories and 99% said "yes, tell me more about what you learned from wearing a continuous glucose monitor." (Not sure why 1% aren't interested, but I'm gonna go with majority vote here!)

I also received A LOT of specific questions about this:

- Why did you choose to wear a CGM?

- Which CGM did you choose?

- What was your average blood sugar?

- How did you get a CGM?

- How much does a CGM cost?

- How bad does it hurt to put in the CGM sensor?

And on and on and on. I received over 60 questions, so I obviously can't answer them all here, but I'll at least cover the biggest and most common questions.

Per usual, what I had envisioned as a short 'n' sweet write up turned into a bit of a research beast. I should know myself by now, ha!

Why did I wear a continuous glucose monitor (CGM)?

There are several reasons.

1. I've been curious about my blood sugar patterns ever since my interesting experience with taking the glucola (glucose tolerance test) during my pregnancy several years ago to screen for gestational diabetes—and my results from home blood sugar monitoring during the few weeks following that test. In short, I wanted to check on my non-pregnant blood sugar balance beyond standard labs.

2. Second, several mamas in my Real Food for Gestational Diabetes Course have used CGMs to better understand and manage their blood sugar levels. In one case, CGM readings revealed really interesting blood sugar patterns overnight and at fasting (first thing in the morning) that ultimately prevented misdosing medications that could have caused hypoglycemia overnight.

In another case, CGM data made a participant realize her blood sugar was spiking sooner and higher than she had anticipated after certain meals. With solely relying on fingersticks to check her blood sugar, she had been missing the "highest highs." She was able to pinpoint what was causing her blood sugar spikes and better tailor her diet/lifestyle (which ultimately helped her stay diet controlled and have the out-of-hospital birth she had hoped for).

In other words, using a CGM was like having a window into their blood sugar patterns. It eased stress, improved their sense of control over what otherwise feels like a rollercoaster of a ride, and helped them better manage their gestational diabetes overall. As a certified diabetes educator, I've found CGMs cut out a huge amount of guesswork for clients and care providers alike.

3. Third, I had comprehensive blood work done a few months ago, which included a variety of metabolic markers. My HOMA-IR, a marker of insulin resistance, was almost too good (indicating favorable insulin sensitivity) and my fasting insulin and blood sugar were relatively low. While my results were overall very good, I was curious about what was going on with my blood sugar on a day-to-day basis.

4. Fourth, I have a family history of type 2 diabetes and reactive hypoglycemia. I know from all of my mindful eating observations that I feel best eating a moderately low carb diet, which probably is more kind to my pancreas (thanks to avoiding major blood sugar spikes). I know that heredity plays a role in your risk for disease, but also that lifestyle is a powerful way to moderate that risk. If we can catch any blood sugar issues very early on, we can take action to help prevent the progression to type 2 diabetes. If I inherited a crappy pancreas (no offense, pancreas… I don't know for sure; I still love you man!), maybe I should take extra precautions?

If I can sum it up in one word CURIOSITY is what made me do this CGM experiment.

How do continuous glucose monitors work?

CGMs use a "minimally invasive electrochemical sensor" that's inserted below the skin to measure blood sugar levels in interstitial fluid (that's the fluid between your cells).

It emits a low frequency signal to communicate blood sugar data to a reader device. Different CGM systems vary in the specifics, but you essentially end up with a vast amount of data on your blood sugar patterns. Instead of relying on fingersticks and a regular glucometer, you can keep tabs on what's happening 24/7 (without having to constantly prick yourself, hallelujah!).

How do you choose which CGM to get?

First off, this is not a sponsored post whatsoever. I had to pay out of pocket for everything (see below). I WISH the manufacturer would have donated one of these things to me since I'm about to give it a ton of free PR. The things I do for science!

I chose the Freestyle Libre for ease, functionality, and cost. Most CGMs require calibration with fingersticks using a glucometer (often with twice daily). Freestyle Libre is factory calibrated, so no need to poke your fingers all the time. This is both a benefit and a limitation of the system. It also tends to be less expensive than other CGMs.

It's way beyond the scope of this post to discuss pros and cons of all CGM systems, so please take up that conversation with your care provider if you're interested.

How do I get a CGM if I don't have diabetes?

Continuous glucose monitors are by prescription only. Yes, they are typically used for people with diabetes. Even 10 years ago, it was pretty rare for anyone other than those with type 1 diabetes to get one, but new technology (that's more accurate and affordable), provider awareness, and consumer demand has driven many non-diabetics to try out CGMs for themselves.

I simply talked it over with my doctor and he was happy to write a prescription for one. I have a feeling that my professional work as a dietitian and certified diabetes educator specializing in gestational diabetes (as well has our talk about some research studies on GD I'm consulting on) helped sway the decision in my favor.

If in doubt, it doesn't hurt to ask! If your provider errs on the side of preventative medicine or functional medicine, I'd wager they'd be more likely to recommend a CGM.

UPDATE: One other option for obtaining a CGM is to use a company like Levels, which will connect you with a provider to see if you qualify for a CGM. This was not an option at the original publishing of this article, hence the update here. Use this link to get to the top of the 100k+ waiting list.

How much does the Freestyle Libre cost?

This will vary by your location, your pharmacy, and whether insurance covers it or not. For me, insurance did not cover it. The only pharmacy near me that carried the Freestyle Libre was Walmart, which apparently has great pricing on prescriptions.

The Freestyle Libre has two components to function: a reader and a sensor.

Reader: $79.45 (you only buy this once)

Sensor: $43.66 (you have to replace this every 10-14 days)*

Another colleague who has one (but lives in a different part of the U.S.) paid $110 total for the reader and her first sensor; replacement sensors were ~$40. As I said, this will vary based on where you live.

The cool thing is the reader doubles as a regular glucometer, so if you don't have a blood sugar meter already, you can use this for double duty. It uses the Freestyle Precision Neo test strips.

*At the time of writing the 10-day sensor is the current norm in the U.S. They also manufacture a 14-day reader that was recently approved by the FDA (which, for reasons beyond me, is already the standard in other countries).

UPDATE: The 14-day sensor is now available in the United States. A reader device is not necessarily needed as most smart phones can serve as a reader with a special app.

Did it hurt to insert the Freestyle Libre sensor?

I'll admit, the insertion of the sensor was something I feared most. The thought of having a sensor under my skin freaked me out, then thinking about how I would get it there freaked me out more.

Luckily, they've designed the Libre to be pretty foolproof. The sensor comes with a contraption that takes all the guesswork out of insertion. It's essentially a plastic device with a spring-loaded needle—ok, that sounds scary when I write it out…. It's a plastic thing that attaches to the sensor. You line it up on the right area of your arm and push down. Before you can blink, the spring-loaded needle thing has poked a hole, retracted, and in its place left the sensor attached to your arm.

I swear it was just as easy as a fingerprick. It did not hurt at the moment, but it does make a tiny wound where the sensor is implanted under your skin. For me, that was a little bit sore, like a very very very dull ache (pain scale 1/10) the next day, akin to the feeling after getting blood drawn.

Short answer: no, it doesn't hurt.

Was it uncomfortable to wear a CGM?

Not really. For the Freestyle Libre, the sensor is worn on the back of the upper arm (tricep area). The part of the sensor that's external is a little larger than the size of a quarter. The internal sensor is ~ a quarter inch long and aside from the very mild ache I had the day after placement, it didn't bother me.

I was worried the adhesive on the sensor would irritate my skin, as I'm very sensitive to the adhesive on bandages/tape, but this was surprisingly a non-issue for me.

After a few days, I became less aware of something being stuck on my arm. I'd accidentally bump it every once in a while or catch it on a shirt as I was getting dressed or notice it as I rolled over in bed, but it otherwise it wasn't bothersome.

I will say, I'm extremely grateful that I don't have to wear one at all times. I can only imagine what my friends/clients with type 1 diabetes have to put up with having a CGM and often an insulin pump constantly attached to their body. Just one more thing to always have on the back of your mind.

Was the CGM easy to use?

This shows how easy it is to take a real time blood sugar reading from the Freestyle Libre continuous glucose monitor. Press the button on the reader, bring it close to the sensor on your arm, and voila!

What are normal and abnormal blood sugar levels?

This is a surprisingly hard question to answer. If you go by American Diabetes Association standards, "normal" blood sugar is less than 100 mg/dl fasting (such as first thing in the morning before eating), and less than 140 mg/dl two hours after eating.

In general, they state that non-diabetic people have blood sugar in the range of 70-130 mg/dl.

For an official diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, fasting blood sugar would be 126 mg/dl or higher, and 200 mg/dl or higher 2 hours after a 75 gram glucose tolerance test (and/or A1c of 6.4% or greater).

For an official diagnosis of prediabetes, blood sugar levels are below the criteria for type 2 diabetes, but above 100 mg/dl fasting and 140 mg/dl 2 hours after a glucose tolerance test (and/or A1c of 5.7% of greater).

What is not specified in these guidelines is how high it's "normal" to see your blood sugar spike after meals. Since these guidelines are focused on diagnosing and treating diabetes/prediabetes, they don't give us much insight into truly normal blood sugar levels. I'll explain more on this later in this post.

Lily, what did you learn about your blood sugar from wearing a CGM?

This is obviously the reason you're here. This is the reason I did the whole CGM experiment in the first place.

In some ways, my results were surprising and in other ways, exactly as I would expect. My goal was to test my regular diet and see how my blood sugar fared with my usual low-ish carb, real food, mindful eating approach. There were a few unusual meals, including Thanksgiving dinner and the morning I intentionally ate oatmeal (more on that later!); otherwise, I was just eating as I always do.

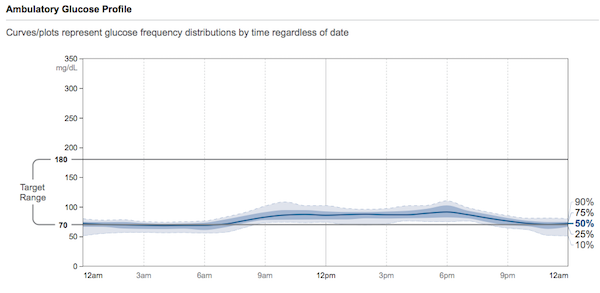

My average blood sugar over the 10 days was on the low end: 79 mg/dl. No, I did not have symptomatic hypoglycemia. The lower average was due to my blood sugar running primarily in the 60's and 70's at night ("fasting"). During the day, my blood sugar mostly hung out in the 80's-90's with occasional peaks depending on the carbohydrate content of my meals.

My lower carb real food meals rarely spiked me above 100-110. I had a few higher spikes from meals that included a small to moderate amount of carbs, such as: a slice of real sourdough, rice, potatoes/sweet potato, or hidden sugar (psst – scroll down for my oatmeal experiment).

For example, we had some Thai food from a local Thai restaurant and I'm pretty sure the curry and sauces have sugar in them (it's pretty standard in Thai cooking to add sugar). I was surprised after eating a big bowl of curry with chicken and vegetables and the tiniest serving of white rice (we're talking ⅓ cup, friends), to see my blood sugar spike to the 130's.

Even though the rice was leftover (therefore had been cooled for >12 hours, which converts a portion of the starch into "resistant starch", which is praised as healthful for our microbiome and less-impactful on blood sugar levels), it clearly still spiked my blood sugar. I can personally feel my blood sugar spiking at fairly low levels with symptoms like racing heart and jitteriness. It's subtle, but noticeable, probably because my blood sugar tends to run stable in the lower range.

I repeated the same Thai food leftover meal the next day, just without the rice (so I'm sure there was still hidden sugar in the curry) and my highest peak was only 105. White rice and I are apparently not friends, even in portions that provide only 20 grams of carbs.

Sorry, everyone who's #teamwhiterice. It doesn't work for me.

Does my blood sugar run low, are the criteria for "normal blood sugar" wrong, or was my sensor off?

I'll be honest, seeing my numbers average on the low end made me question a lot of things.

First off, is my blood sugar truly low? Maybe. Last time I had blood work drawn (meaning a venous blood sample), my fasting glucose was 68 mg/dl. This was after a 14 hour fast (not intentional; my appointment got pushed back that day).

This makes me think the Freestyle Libre readings were accurate. My fasting insulin levels were also on the low side, which is physiologically to be expected when fasting. The body is going to preferentially switch to burning fat/ketones and meanwhile both glucose and insulin will decrease during extended periods without food.

I spot tested with my glucometer a few times to check the accuracy of the CGM. It was always within 10 mg/dl of my fingersticks, but interestingly the "lower" values from the CGM tested 5-10 points higher on fingersticks, and the "higher" values on the CGM tested 5-10 points lower when double checked with the fingersticks (in other words, CGM made my lows look lower and my highs look higher than was indicated by my blood sugar meter).

My readings were still within an acceptable range of variation, but I did dig up a few articles in the medical literature that suggest that Freestyle Libre readings can be a little off, either from a factory calibration error or other factors. Even so, observing the overall patterns in my blood sugar was invaluable.

It's also well-known that interstitial glucose (what you measure with a CGM) can have a lag time compared to capillary glucose (what you measure with a finger stick). That in and of itself could explain the slight discrepancy I observed between fingersticks and CGM readings.

If I assume that my blood sugar truly runs on the lower end of the normal range, maybe our current accepted "norms" for blood sugar aren't perfect.

As with most lab values, the normal range is defined by a certain number of standard deviations from the average. I may be a person who naturally runs on the lower end of the range.

Nonetheless, the research thus far suggests that:

"In individuals with normal glucose tolerance, glycemia is maintained within a narrow range between 68.4 and 138.6 mg/dL." (Diabetes & Metabolism Journal, 2015)

I tried to dig up some data on blood sugar patterns in hunter-gatherers (modern-day, obviously), to shed some light on the issue.

In the Hadza (people who are indigenous to Tanzania), researchers have yet to observe fasting glucose readings above 85 mg/dl. Similarly, fasting glucose levels from the Shuar (indigenous people of Ecuador and Peru), run on the lower side, with "fasted glucose levels among rural Shuar men (73.6 ± 13.2, n = 32) and women (82.1 ± 21.2 mg dL−1, n = 49)." (Obesity Reviews, 2018)

That means some indigenous people subsisting on their traditional diet have fasting glucose levels as low as 60 mg/dl.

Perhaps my blood sugar readings in the 60s and 70s at night aren't so low after all?

Are you sure your blood sugar is running low? Enter: OATMEAL.

Another interesting finding was my oatmeal test. Now, for the duration of the experiment, I ate my normal breakfast, which is typically some variation of 2 eggs cooked in butter or lard, vegetables (usually rotating between kale, broccoli, mushrooms, onions, etc.), and possibly some breakfast meat, like sausage or bacon. Alongside this, I have black tea (unsweetened) with heavy cream. [Read: I eat a low carb, high fat, moderate protein breakfast.]

This style of breakfast was a dream for my blood sugar, essentially flatlining it in the 80s or 90s. It's also excellent for my energy levels, satiety, and productivity (low carb + real food + mindful eating for the win!). I can easily go for 3-5 hours without getting hungry (depends on the day and how active I am), which is nothing short of a miracle for someone who used to be a huge snacker.

There's a reason I tend to return to a variation of this day after day. Even when I added a small slice of sourdough one morning and ½ cup of leftover roasted potatoes another morning, my blood sugar didn't exceed 100 (the magic of not eating "naked carbs").

I started to wonder if I was just super insulin sensitive in the morning or maybe had more wiggle room for carbs.

So, the final day of my CGM sensor, I decided to eat a breakfast similar to the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics' sample meal plan in their pregnancy guidelines. Their meal plan is oatmeal, skim milk, and strawberries. In other words, all carbs.

(For those of you familiar with my book, Real Food for Pregnancy, this is the same meal plan that I use to make a comparison on the nutrient-density and macronutrient ratio compared to my real food meal plan. This excerpt of the book is included in the free chapter download; see the bottom of this post or this page to get it.)

I don't have skim milk in the house (and I never will), but I do have whole, grass-fed milk for my son. I also didn't have strawberries, but I have raspberries, which are nutritionally similar. So I whipped up measured portions of rolled oats (1/2 cup dry, which is 1 cup cooked) prepared with water, a little milk poured on afterwards (I'm really not a fan of straight up milk, so I only used a few Tbsp), ½ cup raspberries, and because it was in-edibly plain, I added 1 measured teaspoon of honey (not heaping). Total carb count was 45g.

All things considered, this was NOT a large bowl of oatmeal and it was essentially NOT sweet, despite adding a little honey. (I say this to point out that the average person adds A LOT of extra sweeteners to their oatmeal, either with sugar/honey or dried fruit. My version would be unpalatable to many people.)

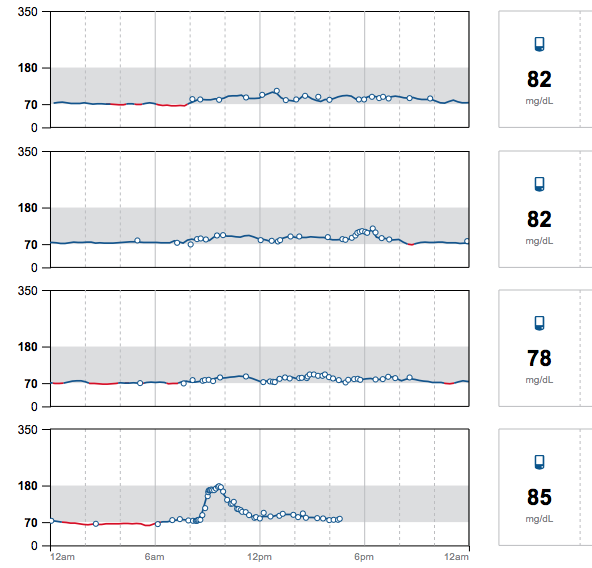

At first, I thought my blood sugar was doing ok after the oatmeal, but I then watched with horror on my Freestyle Libre as the readings climbed. When you scan the sensor, the Freestyle Libre reader shows an arrow next to the numerical reading with an up, down, level, or slightly up/down error, indicating your real time blood sugar trends. This was the ONLY time during the entire 10 days that I saw the straight up arrow, indicating my blood sugar was rising FAST.

My blood sugar went from 74 to a peak of 178 in an hour. By two hours, I was down to the 120s and by three hours, finally back down to 100.

This perfectly illustrates why I preach "no naked carbs" (meaning carbs eaten without a source of fat or protein). The spike from oatmeal was 40 points higher than my Thanksgiving dinner, which included stuffing, sweet potatoes, cranberry sauce, pumpkin pie (in other words, the same or more carbohydrates than this unsatisfying, bland oatmeal breakfast). I'd wager that I didn't spike as high from Thanksgiving because there was sufficient fat, protein, and fiber in the meal to slow digestion and absorption of the carbohydrates.

This image shows 4 days of blood sugar data. The first 3 days, I'm eating my regular diet. The last day, I did the oatmeal experiment. See the peak on day 4?

What was interesting, though, is that I got ravenously hungry when my blood sugar started plummeting. Now, this is a mindful eating/blood sugar physiology teaching I've been using in practice for years (go back to my viral post, The Healthy Breakfast Mistake, for a hilarious run down).

It was really interesting to watch it pan out in real time on my CGM. I had always assumed that I wouldn't be hungry until my blood sugar was back down to normal or in the hypoglycemic range, but this experiment showed me that the hunger trigger (for me, anyways) is in response to the impending crash.

I actually didn't end up hypoglycemic in response to this meal, but I literally had to eat something with substance (fat/protein) around the two hour mark (~ 2 oz of leftover grass-fed beef burger patty) to avoid going hangry. That probably stopped me from going into reactive hypoglycemia.

After this oatmeal experiment, I started wondering if my glycemic response to oatmeal was exaggerated or unusual. It's surprisingly hard to find data on blood sugar responses in non-diabetics, especially when trying to examine the "peak" blood sugar response.

As you can recall, as long as blood sugar is back down to 140 mg/dl by two hours after eating, then you're supposedly "in the clear" by conventional guidelines for diabetes/prediabetes. If a study has people measure their blood sugar only at 2 hours, you're likely to miss the peak glycemic response in many people. Moreover, different people peak at different times, so without a million finger pricks or CGM, the results aren't going to be very meaningful.

Blood sugar patterns in non-diabetics

After spending entirely too much time on Google Scholar (this is my M.O. in life), I was able to find some studies on continuous glucose monitoring in non-diabetics (hooray!).

In one study from Stanford, 57 participants—comprised of people with and without diabetes—wore a CGM for 2-4 weeks. (PLoS Biology, 2018)

They stratified the glucose data into 3 subtypes of glycemic variability (essentially, how much a person's blood sugar spiked or dropped throughout the day). The healthiest subjects tended to have the lowest glycemic variability. In other words, their blood sugar stayed within a tightly controlled range for most of the day.

These people tended to have a lower BMI, be younger, and have lower readings of glucose, A1c, fasting insulin, and triglycerides (this resembled my glycemic patterns).

A subset of the study group were given standardized meals to measure the glycemic response. In the test of cornflakes and milk (which is nutritionally similar to my oatmeal breakfast), fully 80% of people without diabetes experienced blood sugar spikes beyond 140 mg/dl (prediabetic levels). Furthermore, 23% of this group saw blood sugar levels exceeding 200 mg/dl (diabetic levels) after cornflakes and milk.

They write:

"It is interesting to note that although individuals respond differently to different foods, there are some foods that result in elevated glucose in the majority of adults. A standardized meal of cornflakes and milk caused glucose elevation in the prediabetic range (>140 mg/dl) in 80% of individuals in our study. It is plausible that these commonly eaten foods might be adverse for the health of the majority of adults in the world population." (PLoS Biology, 2018)

In a press release on the study, one of the authors comments further on the cornflakes result:

"Make of that what you will, but my own personal belief is it's probably not such a great thing for everyone to be eating."

Ya think?

This is the whole argument for a lower carbohydrate diet as a treatment and/or preventative strategy for type 2 diabetes.

They also note that occasional high blood sugar readings (arguably, not ideal), are common, even among people without diabetes:

"Importantly, we found that even individuals considered normoglycemic by standard measures exhibit high glucose variability using CGM, with glucose levels reaching prediabetic and diabetic ranges 15% and 2% of the time, respectively. We thus show that glucose dysregulation, as characterized by CGM, is more prevalent and heterogeneous than previously thought and can affect individuals considered normoglycemic by standard measures, and specific patterns of glycemic responses reflect variable underlying physiology. The interindividual variability in glycemic responses to standardized meals also highlights the personal nature of glucose regulation." (PLoS Biology, 2018)

This study brings into question the overall insistence on using glucose tolerance tests, A1c, and fasting blood sugar to define diabetes, as if it's this black and white diagnosis. (Spoiler alert: it's not.)

Imagine if you could go to the doctor, have a CGM sensor inserted on the spot, then return in 2 weeks to have your data analyzed and graphed using the criteria in this study. It would give us a much more nuanced look into your blood sugar regulation. It would also reveal what foods are great for your blood sugar and conversely, which ones are a glycemic disaster. This would be preventative medicine. Intervene before blood sugar levels are consistently in the diabetic range, before insulin resistance gets too severe, and before beta cell burnout.

Then again, this would be a royal pain for practitioners/insurance companies who like the black and white nature of single tests. I don't think I'll hold my breath waiting for this to become the standard of care.

In another CGM study (this one from Spain), glycemic patterns were tracked in 322 people (both prediabetic and non-diabetic) eating their usual diets, providing 1521 complete days of data. ( Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 2018)

Participants had blood sugar in the non-diabetic range (<140 mg/dl) 97% of the time.

Interestingly though, 73% of participants experienced episodes of high blood sugar in the prediabetic range (and 5% in the diabetic range).

The average amount of time spent above the normoglycemic range (blood sugar over 140 mg/dl) was 32 min per day in the normoglycemic group and 53 min in the prediabetic group. The peak blood sugar reading for non-diabetics averaged 119 mg/dl (compared to 128 mg/dl in the prediabetic group).

Also interesting was that 44% of non-diabetic people in this study had some bouts of "hypoglycemia" defined as less than 70 mg/dl. (This again made me question if 70 mg/dl is really an appropriate cut off for hypoglycemia.)

I think this data highlights just how hard our bodies work to keep our blood sugar in a tightly controlled range 24/7. I don't think a few high readings are necessarily a sign of something wrong, it just shows you which foods force your body to work especially hard to bring those "highs" back to the normal range as quickly as possible.

Blood sugar patterns in non-diabetic people who are morbidly obese

Another interesting dataset I came across was an analysis of CGM data from morbidly obese participants with and without prediabetes (literally these participants were applicants to The Biggest Loser; it's in the study methods) found significantly higher glycemic variability and overall higher glucose levels when compared to CGM data from non-diabetic, non-overweight adults. (J Diabetes Sci & Tech, 2014)

Specifically, prediabetic Biggest Loser applicants had 17.6% of blood sugar readings above 140 mg/dl while non-diabetic Biggest Loser applicants had 11.8%. Meanwhile, non-diabetic adults who are not morbidly obese only experienced 0.3-4.1% of readings above 140 mg/dl.

This data highlights the role that excess body weight plays in blood sugar regulation, even if you "pass" diabetic/prediabetic screenings by conventional standards.

Should we be eating so many carbs?

All things considered, I think what these studies highlight is that modern, high-carb diets are a mismatch for our physiology. The research has a name of it: evolutionary discordance hypothesis.

In other words "departures from the nutrition and activity patterns of our hunter‐gatherer ancestors have contributed greatly and in specifically definable ways to the endemic chronic diseases of modern civilization" (Nutrition in Clinical Practice, 2010)

To quote Eric Sodicoff, MD, "CGM is useful to prove that you need to be eating stone age food."

Is there harm—or even benefit—in occasional blood sugar excursions?

Some argue that elevated blood sugar after meals is normal, while others argue that you should aim to keep your blood sugar as "flatlined" as possible. Honestly, I don't know which is true and I don't think we have an easy answer.

Where we need more research is in blood sugar patterns of metabolically healthy individuals. I'd be especially curious to see some CGM data from modern day hunter-gatherers.

We have an abundance of data on the harms of consistently elevated blood sugar (and certainly as a country are observing first-hand epidemic levels of beta cell burnout and insulin resistance). On the other hand, I can see from the perspective of maintaining metabolic flexibility ("testing" your pancreas just like you "test" your immune system during occasional illness, seasonal differences in food availability ancestrally) that it may be harmless to experience occasional blood sugar spikes.

From an ancestral perspective, carbohydrate intake varied seasonally. So It's certainly plausible that having some occasional high blood sugar readings is not a concern, so long as there are spans of time where they can return to baseline (which was likely the case before the convenience of a globalized food supply, grocery stores, and take out).

The key here is that if occasional blood sugar spikes are ancestrally normal, it was also ancestrally normal to have periods of time WITHOUT blood sugar spikes. That is something that is missing from modern life for most of us.

Moreover, as I cover in Real Food for Pregnancy, the most comprehensive assessment of dietary patterns in modern-living hunter gatherers shows that they eat far fewer carbohydrates than we do with an average of 16-22% of calories from carbs. Compare that to our dietary guidelines, which push 45-65% of calories from carbs. It's just A LOT of carbs for the human body to process.

Studies looking at glycemic variability, which refers to swings in blood glucose levels, tend to point towards minimizing the frequency of blood sugar spikes for heart health:

"Since 1997, more than 15 observational studies have been published showing that elevated [postprandial glucose], even in the high nondiabetic [impaired glucose tolerance] range, contributes to an approximately 3-fold increase in the risk of developing coronary heart disease or a cardiovascular event [13]. Moreover, the meta-analysis of the published data from 20 studies of 95,783 individuals found a progressive relationship between the glycemic variability (GV) and cardiovascular risk [49]. In summary, the accumulated data that GV seems to be associated with the development of microvascular complications appear to be impressive." (Diabetes & Metabolism Journal , 2015)

Bigger implications for diabetes and prediabetes

At this time, 49-52% of the adult US population has either diabetes or prediabetes, many of whom remain undiagnosed. (JAMA, 2015) It's estimated that upwards of 70% of people with prediabetes will go on to develop type 2 diabetes. (PLoS Biology, 2018)

A 2018 analysis of the most recent National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data found that only 12% of Americans are "metabolically healthy." TWELVE PERCENT. (Metabolic Syndrome & Related Disorders, 2018).

That means 88% of Americans are NOT metabolically healthy.

By the way, their definition of metabolic health included fasting blood sugar, A1c, blood pressure, triglycerides, HDL cholesterol (checking to see they had sufficient "good" cholesterol), and waist circumference. I was pleased to see they left total and LDL cholesterol as well as BMI out of their criteria, as these are less reliable markers of overall health.

I have no doubt that if I continued to eat high-carb meals for my lifetime (like oatmeal), pushing my blood sugar levels to prediabetic levels again and again and again… gradually resulting in a breakdown of my insulin sensitivity, I would become one of these statistics. Furthermore, eating this way leaves me feeling like garbage. It makes me crazy hungry for all the wrong foods as my poor body attempts to regulate blood sugar between spike after spike.

Fortunately, I don't have to go down that path because this experiment has highlighted just how crucial a lower-carb, real food diet is to maintaining blood sugar balance, even for people like myself, who supposedly have normal glucose tolerance. If you watch the spectacular results of the Virta program or similar diabetes interventions using a lower carbohydrate approach, it's just common sense. (Diabetes Therapy, 2018; JMIR Diabetes, 2018)

Even without blood sugar data, simply relying on mindful eating is what keeps me eating this way. If I feel good, if my energy is solid, if my mind is clear, if I'm sleeping well, if my menstrual cycles are normal, if my digestion is happy, if my thyroid is normal… obviously my body is communicating that this works for me. I can check all of those boxes (well, now that my toddler sleeps, I can check the sleep box… hooray!).

Furthermore, all my other lab markers of blood sugar and insulin regulation are good. Fasting insulin is low, HOMA-IR (a marker of insulin resistance) is good, leptin:adiponectin ratio is good (this is another surrogate marker of insulin resistance), A1c is good, all lipids are optimal, CRP is low, BMI is normal, etc.

The point is that even if you're "metabolically healthy," your blood sugar can still spike pretty high if you eat a bunch of naked carbs.

My oatmeal experiment made that crystal clear.

Why is carb tolerance so individual?

Everyone's carb tolerance is different and that's what is so cool about wearing a continuous glucose monitor. For me personally, total carbohydrate intake at meals was the biggest determining factor of my blood sugar response. Non-starchy vegetables, which contain small amounts of carbohydrates but a higher proportion of fiber (meaning low in net carbs), didn't spike my blood sugar whatsoever, even at meals with BIG portions of non-starchy vegetables.

I was able to tolerate potatoes, sweet potatoes, winter squash, beans, real sourdough bread, and fruit (eaten whole) without a spike my blood sugar so long as I ate them in reasonable portions (about half a cup at a time) and alongside fat and protein (thus lowering the glycemic load) and lots of non-starchy vegetables (fiber & phytochemicals). I learned that rice, oatmeal, and hidden sugar did not work well for my body.

It could be that the latter sources of carbohydrates are "acellular," which some research argues has a more severe glycemic and inflammatory response.

It could be that my microbiome has some preferences of its own (yes, the bacteria in your gut appear to play a role in your blood sugar).

It could be that I inherited a pancreas that doesn't enjoy pumping out big boluses of insulin (could be from generations past or even my mom's diet while I was in utero). Yay, #epigenetics.

Technically, it doesn't matter what the mechanism is. What matters is that I can identify the foods that spike my blood sugar and make a choice as to if I eat them, in what portions, and how often.

Final thoughts on my CGM experiment

There's a lot of "noise" in the nutrition world.

People telling you that you need to eat a certain macronutrient ratio. People telling you that going low carb is guaranteed a bad choice for women (there's some nuance here, but I overall disagree so long as you're eating sufficient quantities of nutrient-dense food, managing your stress, and not over-exercising). People telling you that you must go plant-based or carnivore.

Essentially we have a lot of people telling you that whatever you're doing is wrong.

Wearing a CGM cuts through all the noise.

Eating for better blood sugar balance has carryover benefits to the rest of your health. I think the key with CGM is to try to observe other symptoms and how they relate to your glycemic response to a meal.

Note how your energy and hunger/fullness levels relate to your blood sugar.

Note how your sleeping patterns affect your blood sugar.

Note how eating to satiety vs. eating to discomfort affects your blood sugar.

Note how snacking or not snacking affects your blood sugar.

Note how eating an earlier or later dinner affects your blood sugar.

Note how exercise, stress, meditation, deep breathing, light exposure, nutritional supplements, etc. all affect your blood sugar.

Then play around with all of these factors to make adjustments to bring your blood sugar back to a healthy range.

I see CGM as a huge opportunity for preventative medicine. Here's to hoping this technology becomes available more widely, for a lower cost, and without a prescription.

If you have questions or comments on CGM, please share them below and I'll do my best to address them here or in a future blog post/interview.

Until next week,

Lily

PS – I know a big portion of my audience is interested in pregnancy. If you're curious how blood sugar balance is affected by pregnancy, I encourage you to check out Ch 9 of Real Food for Pregnancy, where I sort through all the pros/cons of the different testing options for gestational diabetes and how blood sugar patterns naturally shift during pregnancy.

Also, see this post that explores 9 myths about gestational diabetes.

Research into using CGM as a replacement for glucose tolerance tests are underway, so we'll hopefully have more insight into this as a screening option for gestational diabetes sometime in the future.

References

1. Suh, Sunghwan, and Jae Hyeon Kim. "Glycemic variability: how do we measure it and why is it important?." Diabetes & metabolism journal 39.4 (2015): 273-282.

2. Pontzer, H., B. M. Wood, and D. A. Raichlen. "Hunter‐gatherers as models in public health." Obesity Reviews 19 (2018): 24-35.

3. Hall, Heather, et al. "Glucotypes reveal new patterns of glucose dysregulation." PLoS biology 16.7 (2018): e2005143.

4. Rodriguez-Segade, Santiago, et al. "Continuous glucose monitoring is more sensitive than HbA1c and fasting glucose in detecting dysglycaemia in a Spanish population without diabetes." Diabetes research and clinical practice 142 (2018): 100-109.

5. Salkind, Sara J., et al. "Glycemic variability in nondiabetic morbidly obese persons: results of an observational study and review of the literature." Journal of diabetes science and technology 8.5 (2014): 1042-1047.

6. Konner, Melvin, and S. Boyd Eaton. "Paleolithic nutrition: twenty‐five years later." Nutrition in Clinical Practice 25.6 (2010): 594-602.

7. Menke, Andy, et al. "Prevalence of and trends in diabetes among adults in the United States, 1988-2012." Jama 314.10 (2015): 1021-1029.

8. Hall, Heather, et al. "Glucotypes reveal new patterns of glucose dysregulation." PLoS biology 16.7 (2018): e2005143.

9. Araújo, Joana, Jianwen Cai, and June Stevens. "Prevalence of Optimal Metabolic Health in American Adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009–2016." Metabolic syndrome and related disorders (2018).

10. Saslow, Laura R., et al. "Outcomes of a Digitally Delivered Low-Carbohydrate Type 2 Diabetes Self-Management Program: 1-Year Results of a Single-Arm Longitudinal Study." JMIR diabetes 3.3 (2018): e12.

11. Hallberg, Sarah J., et al. "Effectiveness and safety of a novel care model for the management of type 2 diabetes at 1 year: an open-label, non-randomized, controlled study." Diabetes Therapy 9.2 (2018): 583-612.

Source: https://lilynicholsrdn.com/cgm-experiment-non-diabetic-continuous-glucose-monitor/

0 Response to "Continuous Glucose Monitoring System Graph Non Diabetic"

Post a Comment